Free

software on the server end of an IT infrastructure is quite common in

Germany.[2] What makes the LiMux project stand out is that the

Bavarian capital Munich (1.3 million inhabitants) will migrate 14,000

PCs and laptops of its public employees to non-proprietary software. While

this is not an economically large or particularly technically complex

undertaking, it is the largest deployment of GNU/Linux and OpenOffice

in the public sector so far, and this symbolic value turned it into one

of the world’s highest profile migration projects. Like the fall of the

Berlin Wall, LiMux signals to public and private decision makers around

the world that life beyond the existing order is possible.

Free

software on the server end of an IT infrastructure is quite common in

Germany.[2] What makes the LiMux project stand out is that the

Bavarian capital Munich (1.3 million inhabitants) will migrate 14,000

PCs and laptops of its public employees to non-proprietary software. While

this is not an economically large or particularly technically complex

undertaking, it is the largest deployment of GNU/Linux and OpenOffice

in the public sector so far, and this symbolic value turned it into one

of the world’s highest profile migration projects. Like the fall of the

Berlin Wall, LiMux signals to public and private decision makers around

the world that life beyond the existing order is possible.

The external driving force behind the City Council‘s migration decision was—Microsoft. By discontinuing support for its operating system, Windows NT, Microsoft forced Munich‘s IT administration to plan a major overhaul of its operating software base. Without further official support, Munich’s workstations would quickly become obsolete, unable to reliably run new hardware, new software, or simply new versions of existing software. The municipality had no choice but to migrate to an OS with continuing support. WindowsXP, Microsoft‘s successor to NT, was a leading candidate. By changing its licensing policy for XP from a sales to a lease model, however, the company raised the concerns of budget managers about the rising total cost of ownership (TCO) of the software. A third and ultimately very important factor, identified by Munich's CIO, Wilhelm Hoegner, was that WindowsXP and its components regularly call home. It is unclear what kinds of data are transferred to Microsoft during these contacts, but Hoegner argued that the strict privacy obligations of the public administration made such uncertainty unacceptable).[3]

Within the municipal administration, the driving force behind LiMux is Wilhelm Hoegner, Head of AfID (Amt für Informations‑ und Datenverarbeitung / Department for Information and Data Processing), the central IT service provider for the City of Munich. Hoegner, 53, is a member of the Social-Democratic Party (SPD), an electrical engineer by training, and by no means an anti-Microsoft crusader—despite press depictions of him as a rebel and “a punk in a suit." In fact, he has worked with the company and its products for years, and has been just as critical of free software. His first proposal for FOSS migration to the Munich City Council in February 2002 met with unanimous rejection. Politicians from all the parties resisted the idea of a switch from a time-tested office suite to new software.

Were they right? Is free software only suitable for server-side functions operated by IT professionals—in Munich’s case, dating back to 1995—or could end-users also learn to work with it? In 2002, Hoegner decided to test his concerns on a randomly selected user group—his wife, Dagmar. When Dagmar quickly developed competency with OpenOffice, “a new, Microsoft-free world took shape for the first time” in Hoegner’s mind.[4] With Hoegner’s unambivalent support, a strong alliance between the technical and the political leadership of Munich City began to grow.

The process preceding the migration had three phases. In November 2001, the City Council decided to evaluate the available alternatives in operating systems (OS) and office suites. In April 2002, it commissioned a consulting company to conduct a study of various possible client configurations.

Based on the results of this first phase, the City Council decided in May 2003 to move its IT systems to free software and web-based applications. The critical arguments for free software were greater vendor independence, leading to more competition in the software market; the future-proofness of open protocols, interfaces, and data formats; and improved security through greater transparency. For users, the greater stability of their workspace computers is expected to be the biggest advantage. Microsoft responded by offering large price reductions on Windows XP and Office, but the long-term advantages of vendor independence weighed more heavily than short-term savings. The Council then commissioned the development of a detailed plan for the migration, which was conducted by AfID together with IBM and SuSE/Novell.

In June 2004, the Council gave its final go-ahead and the third phase, the migration, began. "The migration decision of the municipality of the German city, Munich, is a clear political statement."[5] In spite of their decisiveness, city officials are cautious about predicting success, and chose to conduct a “soft” migration over a period of five years. Throughout, they were conscious of the challenges and costs of retraining—a problem avoided when a user community jumps from minimal IT infrastructure to widespread GNU/Linux adoption (as in the Extremadura case documented by Rishab Aiyer Ghosh in this report.)

A software transition of this scale was unprecedented in the European public sector, and has been widely covered by the press. According to many observers, the conversion of Germany's third largest city government to free software for the desktop is likely to have a network effect and to lead to a wave of other conversions in Germany's public sector as well as in other municipal governments across Europe. Many user communities feel the same pressure from Microsoft’s abandonment of NT support and changing licensing policy, the same desire to escape the thumb-screws of increasing costs, the same sense of dependency on MS file formats, and worries about security.

Given the symbolic importance of the Munich case, heavyweights like Microsoft and IBM entered municipal politics, vying for votes on the council. As the Munich experiment attracted wider attention, it became a test case in the global politics of free software.

Background: The Growing Acceptance of Free Software

The City Council of Munich had long been a social-democratic oasis in the right-wing state of Bavaria. Currently governed by a red-green coalition, it tends to echo the generally strong support for free software found on the federal level. Federal support for FOSS goes back several years. The 2002 decision to migrate the servers of the Bundestag (the First Chamber of the German Federal Parliament) to GNU/Linux drew significant attention, as has the migration of the Federal Ministries of the Interior, Economics, and Consumer Affairs. These leading adopters have paved the way for a wide range of other migrations of public offices, municipalities and private companies.

Among these public agencies, the Federal Bureau for Finances (Bundesamt für Finanzen -- BfF) runs all its Internet and intranet applications on Linux. The Anti-Trust Office, the Monopoly Commission, the Federal Bureau for Privacy Protection and others have partly or wholly switched to Linux and other free software. The Surveyor‘s Office of the State of Bavaria announced in June 2003 that all of its 79 departments, including its 3,000 desktops, are running Linux exclusively. The reasons cited include cost but also security.[6]

Other German cities have been exploring the same path Munich is taking. Indeed, the small town of Schwäbisch Hall in Baden-Würtemberg (36,000 citizens) can rightfully claim to have been first. It began to migrate its servers in August 2002, and in November 2004 announced that it would include all of its 400 desktop PCs as well. This decision led to requests from more than 30 municipalities in Germany and from others as far the US and Chile. Such actions tap extensive and often unanticipated anti-Microsoft sentiment.[7]

In addition to the technology departments of government agencies, it is often the financial departments that urge migration to free software. The Budget Audit Office of the German state of Bavaria (Bayerischer Oberster Rechnungshof) recommends free software for cost reasons wherever possible. Its Annual Report for 2001 devotes a whole chapter to criticizing the growing dependence on Microsoft products resulting from its new licensing practices, and also provides guidance on opportunities for using free software in the public administration. The document cites numerous examples of public offices that are already utilizing free software (e.g. the State Bureau of Criminal Investigation, the Surveyor‘s Office, and the Building Surveyor‘s Office), and describe how these migrations save millions of German Marks. It strongly recommended FOSS on servers, and pilot projects for FOSS on the desktop. It argued that more attention should be paid to FOSS in schools.[8] In its 2004 Report, the Audit Office again urged that FOSS be examined for the IT infrastructure needs of schools.[9]

These official recommendations began to bear fruit. Following the 2001 report, the State Parliament of Bavaria decided to include consideration of FOSS solutions when choosing IT systems for the public administration.[10] In June 2002, the Federal Interior Ministry announced a cooperation agreement with IBM regarding the introduction of free software into public administrative offices—including special prices for hardware and software purchases. Half a year later, some 500 public offices on the municipal, state and federal level had made use of that agreement, and many more were standing in line.[11]

A month later, the Coordination and Consultation Bureau for IT in the Federal Administration (KBSt) of the Interior Ministry released a “Migration Guide” for both servers and desktops, gathering experiences from existing migration projects and giving detailed advice for decision makers in public administrations.[12] These reports and aggregated case studies have gone far in normalizing the adoption of FOSS solutions in Germany, building outward from innovative public administrations toward other public and private constituencies.

Munich’s Starting Position

In Munich, some 16,000 public servants make use of 14,000 PCs and Laptops. In 2004, all were running Windows NT 4.0 and Microsoft Office 97/2000. Roughly 300 other standardized software products are also in use, including web-browsers, schedulers, and clients for Siemens BS2000 and Novell. In addition, about 170 specialized applications are used, i.e. software either specially written or customized for the needs of the municipal administration. Some of these are large scale systems, such as those used by the motor-vehicle registration office. About half of these are macros, forms, and other add-ons linked to MS Office applications. The development of such systems is usually contracted to local small‑ and mid‑sized enterprises (SMEs). Finally there are central server-based applications like databases (Oracle under Unix & Adabas/Natural under BS2000), file services (Novell Netware & Sun PC-Netlink), e-mail (Critical Path), calendar (Oracle), fax (Top-Call) and X.500 directory services (Critical Path).

Plans for the migration were simplified by that fact that MS backoffice components are not used in Munich, but complicated by the desire to continue using a number of specialized applications currently running on the Siemens BS2000 mainframes. Specialized hardware, like plotters and I/O devices, also added complexity to the migration.

Overall, the municipality has 17 IT administration centers, with independent data processing and different requirements for operation, user administration and support. The Department for Information and Data Processing (AfID) itself has five departments with 237 employees, and operates two of the computing centers. Procurement and strategy is arranged centrally, but operation and planning is done locally. Software allocation, security management and user help desks are not standardized. The migration is seen as a chance to consolidate these services.

Framing this agenda was a simple financial reality: the City of Munich, like most German municipalities, had no dedicated financial resources for the migration. It would all have to be done within existing operating budgets.

First Phase: Evaluating the Alternatives

On November 14, 2001, the Munich City Council decided to evaluate operating system and office suite alternatives. On April 17, 2002, it commissioned a study (by Unilog Integrata Consulting GmbH, with the support of AfID) of the possible configurations of the client systems for municipal desktops, which the consulting agency conducted from August to December 2002 (with an addendum in July 2003). The aims of the study were, first, to determine the current state of Munich’s IT infrastructure (with the help of a questionnaire), and second, to evaluate possible alternative configurations on the grounds of technical feasibility, cost effectiveness and a number of qualitative and strategic criteria related to the city’s understanding of its long term infrastructure needs. The alternatives were:

1. MS XP + MS Office XP

2. MS XP + OpenOffice

3. GNU/Linux + OpenOffice

And two transitional solutions:

3a. GNU/Linux + OpenOffice + PC Emulation (WINE / VMWare)

3b. GNU/Linux + OpenOffice + Terminal Server

Both transitional solutions presented architectural and operational complexities, not least with respect to security and an increased need for training. They were therefore considered undesirable as such and only to be deployed where no other solution could be found.

Although the widespread use of specialized applications presented a potential challenge, these were already scheduled for replacement by 2007, independent of the migration. Unilog therefore assumed that both standard and specialized applications, in the course of the usual “change of generation,” could be replaced without additional effort. Staying within the Microsoft world would mean that some of this software could continue to be used but, even in that case, updating from Office97 to OfficeXP would, by Unilog’s estimate, require the adaptation or re-writing of about 20% of existing macros, forms, and other specialized tools.

Finally, Unilog assumed that both XP and Linux would need PCs with a minimum processor speed of 500 MHz and main memory of at least 256 MB, meaning that half of the PCs currently in use would have to be replaced regardless of the choice. For peripheral hardware like printers, scanners, and devices for disabled persons, it was expected that in more cases drivers would be available for XP than for Linux.

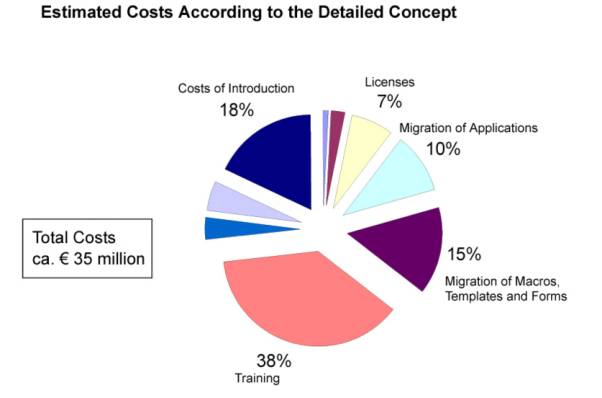

Unilog calculated the total cost of migration, including initial and operational costs during the first four years, for the five alternatives:

1. MS XP + MS Office XP 34.18 million €

2. MS XP + OpenOffice 39.75 million €

3. GNU/Linux + OpenOffice 45.77 million €

3a. GNU/Linux + OpenOffice + PC Emulation 35.94 million €

3b. GNU/Linux + OpenOffice + Terminal Server 50.00 million €

One of the largest factors in the XP/XP solution is the licensing cost of € 7.65 million until 2007. A small fraction of this sum is for the initial investment; the bulk represents the continuing costs of the Enterprise Agreement. In any of the scenarios, training makes up more than half of the total costs. All-MS solutions fared best in this category, leading Unilog to the conclusion that—on a cost basis alone—XP/XP offered a slight advantage.

But the City Council also asked Unilog to consider strategic and qualitative criteria in its recommendations that could not be easily expressed in monetary terms. These criteria included the effort required to fulfill the legal requirements associated with software infrastructure, like privacy laws, the impact on IT security, the attractiveness of work conditions for staff, the effect of complexity on IT maintenance, and the impact on external communications partners. They also included values like open standards, vendor and procurement independence, stability, continuity in purchasing, and the protection of investments. Unilog translated these into a matrix, and assigned a maximum of 10,000 points to each of the five alternatives.

Munich considered dependency on Microsoft to be acceptable as long as substantial independence remained in crucial areas, such the ability to set up backoffice services without MS products. Unilog observed that this independence had become increasingly problematic. Operationally, Microsoft’s product policy had forced Munich to migrate its operating systems even though there was no functional reason to do so. Strategically, the current generation of MS products, because of their high degree of integration, creates pressure to deploy additional MS products. It is, for example, nearly impossible to run clients securely under XP without the corresponding MS backoffice services. Microsoft did garner high scores for the reusability of existing staff know-how and for its de facto standard data formats.

In all other areas, FOSS scored higher. It does not create vendor dependency, as there are many software and service providers—including noncommercial ones like the Federal Office for Security in IT (Bundesamt für Sicherheit in der Informationstechnik -- BSI). It was rated superior with respect to privacy, security, and flexibility; higher in its capacity to improve the manageability of an IT infrastructure, including IT enterprise and IT employee management; and higher in its capacity to reduce the complexity of large systems.

Applying these strategic and qualitative criteria to the five options reversed the results. FOSS scored the highest, garnering 6,218 out of 10,000 points, while the upgrade to Microsoft XP proved the least attractive solution, with 5,293 points. At this point, the study recommended a pure free software strategy. It also warned that migrating more than 14,000 systems and 16,000 users would be risky if not planned and managed properly.

After the release of the report, both Microsoft and the major free software protagonists, SuSE Linux AG and IBM Deutschland GmbH, made new last-minute offers, which Unilog included in the addendum to its study in July, 2003.

Microsoft informed City representatives of a recently concluded general contract with the Federal Interior Ministry in which it guaranteed that it would not abuse its monopoly on pricing and contractual conditions over a period six years. This level of cooperation also promised better responsiveness by Microsoft in implementing public administration standards and interfaces into MS products, and in answering the security demands of the public administration. Even though Microsoft did not discount its products outright, the new arrangement implied a savings of several million Euros. These savings came in several forms—especially better synchronization of update costs with the actual migration of workplaces. By continuing to use the XP configurations until 2010, costs for a follow-up migration after 2007 could be dropped. This offer raised Microsoft’s score on both financial and qualitative strategic criteria.

IBM and SuSE also altered their proposals in ways that lowered the cost estimates for the FOSS solutions. Both companies offered migration consulting for free. SuSE offered an alternative PC emulation with a significantly lower price. Other offers by SuSE were closely linked to the use of SuSE products, the deployment of which had not yet been decided. In the course of this process, the free software solutions also picked up additional points. Improvements to OpenOffice, especially better support for the PDF format, were made available around this time. This was a significant enhancement because of the widespread use of PDF in Munich’s administration, and because of PDF’s emerging status a standard for communication with external partners.

A new round of evaluation of the revised bids yielded roughly equal cost effectiveness for the two major alternatives at a slightly lower cost level for both. In this new round, the XP/XP solution led the FOSS solution by only about half a percentage point. The process proved to participants that the monetary aspects of software choice were highly volatile. In this context, the study framed the migration decision around (1) relatively modest differences in short-term financial costs; and (2) greater differentiators among the mid- to long-term qualitative strategic issues.

The study, in its various phases, was commissioned by the Council and directed primarily at its decision making. This gave Unilog’s recommendations considerable legitimacy. The quality of the study and its clearheaded presentation of the options—including the expected difficulties—were convincing. The serious discussion of FOSS adoption at this stage—even prior to a final decision—did much to increase the comfort level and support for free software among Council members.

Intermezzo: A Visit from Redmond

At the end of March 2003, right before the City Council was to make its final decision on the future of Munich’s IT infrastructure, Steve Ballmer, CEO of Microsoft Corporation, interrupted his skiing vacation in the Alps to visit Munich Mayor Christian Ude (57, SPD) in person to inform him about the new general contract with the Federal Interior Ministry, and about revised offers to the City of Munich.

At about the same time, a number of internal Microsoft documents were leaked to the press, including a confidential e-mail, written a year earlier, that offered a glimpse of the company’s strategy to combat its free competitor. “Under NO circumstances lose against Linux,” wrote Orlando Ayala, then the top sales executive at Microsoft Corporation, in an e‑mail sent to senior executives, including Ballmer, both vice presidents, the company's top lawyers and the general managers of Microsoft operations in Asia, Europe, Africa and the Middle East. As reported by the International Herald Tribune[13] Ayala laid out a strategy to dissuade governments from choosing free alternatives to the ubiquitous Windows operating system, especially on desktop computers. He told executives that if a deal involving governments, educational systems, or other large institutions looked doomed, they were authorized to draw from a special internal fund to offer software at a steep discount—or if necessary, for free. The "Education and Government Incentive Program" was intended to "tip the scales" toward Microsoft in these deals, but the fund was to be used "only in deals we would lose otherwise."

Among these documents was another e-mail written by the head of Microsoft's services department, Mike Sinneck, and sent two days after Ayala’s memo. Sinneck gave details of Microsoft’s “Business Investment Funds,” which earmarked $180 million in 2003 for discounts on consulting services—especially in the server market where GNU/Linux is the company’s strongest competitor.

Yet another confidential document cited by IHT was titled “Open Source Software Government: World Wide Initiative.” This outlined the company’s lobbying program to "prevent adoption of procurement policies favoring OSS." According to the strategic paper, Microsoft employees lobbied ministries in Germany, sought out favorable coverage in the French press, and built "alliances" with opinion leaders in Denmark. Indeed, a range of activities, from hiring the former Senator of Finance of the State of Berlin as the public sector relations manager for Microsoft Germany to regular contacts between Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder (SPD) and Bill Gates[14] could be cited in this context. The German Minister of Economic Affairs, Wolfgang Clement (SPD) appears to be an especially responsive target of MS lobbying.[15]

In an interview with IHT, the chairman of Microsoft operations in Europe, Africa and the Middle East, Jean‑Philippe Courtois, defended the discounts by pointing to the similar tactics of its rivals, e.g. Sun Microsystems’ free distribution of StarOffice. But the anti-trust assessment would be different for Sun than for Microsoft. Under EU law, a company that holds a dominant market position is prohibited from offering discounts that are designed to exclude competitors from the market. With Microsoft already the target of several antitrust investigations by the European Commission, the message the internal documents sent to Munich politicians was clear: a decision in favor of Microsoft under these conditions would be vulnerable to antitrust complaints by competitors.

The surprise visit by Ballmer to Munich Mayor Ude served to draw even more attention to the strategic decision and its potentially far-reaching effects. The external effect was to create a wave of sympathy for the Munich decision makers from many sides, urging them to stick with their original choice of FOSS. Internally, it brought those still hesitating in the City Council firmly behind the anti-Microsoft decision. Since the Council had already announced that the qualitative strategic criteria regarding long-term sustainability would be decisive, Microsoft‘s price reductions were largely moot. Without the Ballmer visit, Hoegner concedes, it would have been more difficult to garner the complete support of the City Council.[16]

Second Phase: Working Out the Details

In spring 2003, a migration planning working group was set up that included members of all municipal offices. Involving them from the very start was seen as crucial to the success of the project.

On May 27, one day before the Council vote, Microsoft offered yet another price reduction of seven million Euros. This came after the Council had closed debate on new offers, and was not taken into consideration. Jens Muehlhaus from the Green Party and other Council member doubted the seriousness and, ultimately, the legality of such last-minute offers,[17] given the recent revelations about secret Microsoft funds for combating Linux. For Munich, the goal of independence from single vendors retained widespread support. On May 28, 2003, the City Council voted to commission a detailed plan for migrating Munich’s client computers to free software and web applications.

Two weeks later, the right-wing CSU opposition party in the Council announced that it would ask the State Government of Bavaria to investigate the decision. As the business magazine “Capital” reported, CSU Councillor Robert Brannekaemper argued that staying with Microsoft products could save the taxpayers millions of Euros. The magazine also quoted a Microsoft Germany spokesperson saying, “we‘ve made the better offer.” The company allegedly set its hopes on the CSU to reverse of the Council decision.[18] One day later, Brannekaemper denied plans to challenge the Council decision.[19]

After the Council decision, project leader AfID, with the support of IBM and SuSE/Novell, spent the next year developing a detailed migration plan—identifying suitable open source products and training options, and determining the technical feasibility and the costs of the migration.[20]

This concept development phase confirmed that the migration to free software would be neither gratis nor easy. The process revealed a range of deficits in the existing software infrastructure, and the migration became an opportunity to address them. Stepping back from these, the project leaders determined that a successful migration required consistent adherence to a number of technological and political principles: (1) applications should be OS-independent; (2) new client-server applications would only be developed or commissioned as web applications according to the J2EE model; (3) cooperation of all software partners would be necessary as software is customized, and as applications are redeveloped; (4) the project had to have the support of both political leadership and heads of the administration; (5) proactive education and involvement of employees would be essential. Hoegner: “I expect the changes concerning the individual workspace to be smaller than some might be fearing. We will do our best to adapt the look and feel of the future workspace to what our colleagues are used to today. Of course, there will be some changes, but with major version changes in Windows or MS-Office in the past we also had to get used to new and different ways of using them. But now we are hoping for higher stability and security as an advantage of the new client operating system.”[21]

During this process, some of the difficulties facing the project also became clearer. Ongoing high priority projects unrelated to the migration would have to continue. IT staff was lacking for many tasks. The small and mid-sized software companies providing applications to the city were still hesitant to embrace GNU/Linux and web-applications. And the question was raised as to whether specifying free software in the procurement procedure might be an inappropriate or unfair requirement. Legal specialists argued both sides—principally over the question of whether requiring FOSS imposed an 'alien’ condition that unduly restricted the pool of potential bidders in software procurement, and that was therefore noncompliant with anti-competition law and the principle of equal treatment. Parties disagreed on how this principle applied to the contracts in question, which combined software procurement with services, and more fundamentally about whether proprietary and free software were “comparable” goods (e.g. in respect to purchase price, follow-up costs, customization, modification). (In antitrust law, only “relatively similar” goods needed to be treated equally.)[22] Ultimately, the city won its argument that FOSS could be categorically required on the basis of determinations about its efficiency for certain purposes—modifiability, security, and so on. This finding may not be definitive, and the question continues to be raised in FOSS adoption discussions elsewhere.

The manner in which the project was conducted was also revised over time. Problems had arisen because the boundaries of the project and the role of the departments had not always been clearly defined. Key persons were not continuously available. And the economic analysis proved to be partly opaque.

The concept and planning phase was primarily directed at IT staff in the administration. Clear support from the City Council and administrative leadership, as well as an active communications strategy, helped generate acceptance among this vital group. By the end of the concept phase, support among IT specialists was high.[23]

Other European Cities: a Domino Effect?

The radiating effects of LiMux, which some had feared and others had hoped for, began to be felt in 2003. Following the example of Munich, Amsterdam announced in October 2003 that it was testing free software for server and desktop applications. In September 2003, the City of Vienna's IT department announced plans to assess the feasibility of a Linux migration for the city administration's desktops. Both cities each have 15,000 office PCs in use. Both projects are now well on their way. In 2005, the Austrian capital will offer half of its computer users the option of switching to GNU/Linux. After a thorough evaluation, a decision will be made regarding an extension of the plan. The estimated cost of the deployment foreseen by the city of Vienna is 1.1 million Euros over five years.[24]

The network effects of free software adoption also began to bear fruit in September 2004, when the IT officials of the cities of Munich and Vienna announced that they would share experience and expertise, and jointly develop free software applications. In particular, they targeted the development of a “public authority desktop” and of open source groupware.[25]

After the French Ministry of the Interior and its agencies had announced a comprehensive desktop migration plan, the City of Paris decided to launch a feasibility study for migration to free software in early February 2004. The study, again conducted by Unilog, concluded that a short-term migration to FOSS would be difficult given the current state of the Paris’ IT infrastructure and systems. However, the Paris City Council nevertheless plans to benefit from the economic advantages of free software and reduce its dependency on Microsoft products in the framework of its € 160 million IT Master plan for the modernisation of the city’s IT systems. A decision on the schedule of a possible migration to FOSS is expected in early 2005.[26]

In May 2004, the City of Rome started to switch the first of its 9,500 desktops to Linux. “This can be defined as a political choice”, said a council communication officer, adding that the debate on free software is being carried out at a national level, and that it brings together politicians from different political camps. A recent directive from the Italian Department for Innovation and Technologies said the adoption of free software could "widen the variety of opportunities and possible solutions in a framework of equilibrium, pluralism and open competition."[27]

The Barcelona City Council voted in July 2004 to migrate the city’s IT systems and desktops to FOSS. The migration, which will be carried out progressively, started with a pilot phase in the social services department. One of the aims is to ensure that all software used by civil servants is available in Catalan—a small market language poorly served by proprietary vendors.[28]

While Spain is in general a strong promoter of free software, with the region of Extremadura running free software on over 70,000 desktops in public administration and over 80,000 in schools (see the contribution by Rishab Aiyer Ghosh), there are also examples of more cautious approaches. On January 5, 2005, the City Council of Valencia announced that it will continue to expand free software on its servers and plans to migrate its eLearning initiative to Linux, but that at present it was not planning any major migration on client computers. The reasons given included resistance from end users to switching from MS Office to OpenOffice, the use by the city of many specialized applications written in Visual Basic, and a lack of FOSS alternatives for applications in areas like computer aided design (CAD) and cartography.[29]

In Northern Europe, the Norwegian city of Bergen declared in June 2004 that it would migrate its education and health services from Unix and Windows to a system built around SuSE Linux.[30] The Danish Municipality of Naestved, in the context of a national pilot project, conducted a successful test of OpenOffice for a year. The outcome led to the unanimous approval of OpenOffice by all municipal organizations, leading the Naestved Municipality to announce, in December 2004, full deployment of OpenOffice. The primary reason offered was its lower cost.[31]

These are just a few impressions of what, from the perspective of proprietary software, no doubt looks like a domino effect. The trend will be further enhanced by network effects and collaboration among the various public sector players, including EU funding. In January 2005, for example, a group of European research institutions and open source software companies announced the joint development of tools to help reduce the complexity and cost of large-scale IT projects. The project, entitled “Environment for the Development and Distribution of Free Software” (EDOS), will develop two tools in particular: a distributed peer‑to‑peer application to help system builders install and integrate software components across dozens or even thousands of PCs and servers, and an automated quality testing suite for GNU/Linux installations or any other large application built on free software. Of the € 3.4 million projected cost of the project, € 2.2 million will be funded by the European Union.[32]

Third Phase: A “Soft” Migration

On June 16, 2004, based on the detailed migration plan, the City Council of Munich voted to move ahead with the migration of its desktop and laptop computers to free software. Only the CSU Councilors voted against the plan. The actual migration phase started with the preparation of an open competitive bidding process for a contract to provide and support the new standard client configuration.

The exact composition of this basic configuration has not been finalized yet. It will certainly consist of GNU/Linux, OpenOffice and Mozilla as browser and mailer. It will likely include the Gimp, although cases might arise where specific plug-ins are required that make it necessary to run Adobe Photoshop in parallel. It will include a CD-burning tool like K3b and packaging software. Many other functions, like calendaring, will be implemented as web applications. For certain functions, solutions still need to be identified. For example, just about every available HTML-editor is in use in Munich’s administration, and everyone is convinced that theirs is the best. Florian Schießl, head of the LiMux project office explains that this will have to be broken down into specific required functions and suitable replacements will have to be found. The original client study was not detailed enough to provide these answers.

The LiMux project has “The IT Evolution" written on its banner,[33] emphasizing that it is not conceived as a revolutionary action but as an evolutionary, step‑by‑step, learning‑by‑doing process. The goal is a “soft” migration over five years, starting with the easy transitions, making use of product life-cycles, and taking the necessary time for the hard problems.

Although there is support by AfID and the working goups, as well as a framework for a common migration path for all of the city’s 17 administrative units, each of those units is responsible for its own migration plan and implementation. The migration will have to be managed mainly by existing staff, without interrupting the operations and services of the departments involved.

The common migration path consists of three phases. In phase 1, Mozilla and OpenOffice will be installed on all workstations, replacing the combination of MS Office and Netscape or MS Internet Explorer. Since OpenOffice can read most existing MS Office files, the migration of data from proprietary to open formats will proceed slowly. The migration teams have not yet defined the standards and open file formats to be used in the end. Phase 1 started right after the June decision and will be concluded for most departments in 2005. The remaining departments will finish by the end of 2006.

Phase 2 involves replacing other non-problematic software (e.g. general office applications) by free software and switching non-problematic workstations to GNU/Linux. Emulation systems for Windows applications (e.g. VM-Ware, Wine or terminal servers) are to be used only when no other solution can be found. The long-term goal is a complete shift to free software. The parallel use of free and proprietary operating systems was considered too demanding on the IT administration. For this reason, it was determined that the existing NT systems be used until the end of their life-cycles.

At first, newly procured PCs will be equipped with Windows NT and, in a few cases, Windows 2000—even if they come with Windows XP pre-installed. During the second phase, most PCs will have GNU/Linux installed from the start. Simultaneously, either native Linux solutions or Web-based services will be developed to replace nonstandard proprietary applications, including applications specific to the public administration. Web implementation makes the applications independent from the operating system and ensures an easy switch to another OS in the future. The migration team assumes that, as a consequence of developing market trends, more and more applications and hardware will be available for open source systems. This phase also started in summer 2004 and will be concluded for all departments by the end of 2007.

In phase 3, the most sensitive software, e.g. software concerning data protection and professional data processing, will be migrated to FOSS. This phase will start for the first departments in 2005 and continue until the end of 2009.

Key to the success of the migration is a well-defined communications process between the migration teams and end-users. Employees were educated early on during the planning phase by intranet presentations, introductory seminars, flyers, demonstration systems and personal discussions about the new system. The goal of the information dissemination is to decrease worries and reservations about the use of free software among public servants. Employee training started with the beginning of the first client replacements.

|

|

Intermezzo: Software Patents

European Commission plans for a directive concerning the patentability of computer-implemented inventions have been hotly debated since the first draft for a directive was released in February 2002. In fact, it gave rise to one of the most powerful single-issue civil society movements of the digital age.[34]

The intention of the Commission is to codify the current state of law in order to harmonize administrative and judicial practices in Europe. It also wants to demarcate them from the current practices in the US where, since a ruling in 1998, computer programs are patentable even if they do not provide a technical contribution to the state of the art.

That an invention has to be novel, of a technical nature, and commercially applicable in order to be patentable is undisputed. At the core of the controversy is the definition of technicity. After a significant number of changes to the Commission draft, the EU Parliament issued a new draft on September 24, 2003. It restricts the patentability of computer programs to those that serve in the automatic production of material goods, and that have an industrial rather than generally commercial applicability. If it were passed it would exclude nearly all computer-implemented inventions from patent protection.

The EU Council issued a new draft in May 2004. Closer to the original Commission draft, this version of the Directive codifies and harmonizes current European jurisdiction. Aside from clarifying that business methods and other methods not based on controlled utilization of forces of nature are excluded from patentability, this draft would not significantly change the current state of law, which has led to the granting of around 30,000 software patents by the European Patent Office so far.

The European Directive cast its shadow on LiMux in July 2004. Green Party City Councilor Jens Muehlhaus, in two motions, asked the Mayor to intervene. In one, he pointed to patent research by the Foundation for a Free Information Infrastructure (FFII) that had indicated that the LiMux basic client configuration might infringe more than 50 existing European patents. On this basis, he asked the Council to investigate the possible consequences of the proposed EU Directive for the LiMux project.[35] In the second motion, Muehlhaus asked the Mayor to urge the Federal Government to reject the Council draft and support the Parliament draft.[36]

On August 4, 2004, the press reported that the City of Munich has put its migration plans on hold due to worries that the looming EU Directive might make the City vulnerable to patent disputes. The night before, Munich's CIO Wilhelm Hoegner had told the members of one of the LiMux mailing lists that the call for tenders for the basic client, planned for the end of July, had been stopped. Pointing to the motion of the Green party, he wrote that the legal and financial risks needed to be assessed before the procedure would resume.[37] Florian Schießl, head of the LiMux project office, sees this statement as an indication of the normal and reasonable procedure to consider all factors before issuing a call for tenders. By calling it the end of LiMux, FFII blew it out of proportion.

Nevertheless, it was evident that such patent infringement assertions against free software could cost the City huge sums in legal and possibly licensing fees, and even disrupt the business of whole departments. Hoegner stated that it was "indispensable" to find out what consequences the EU directive would have on open source software. Uncertainty, he said, “could be a catastrophe for Munich's Linux migration project and for open source in general."[38]

The City administration remained committed to the migration but stopped the call for tenders for the basic system. Furthermore, it decided to commission a legal study on the risks of software patents and to demand clarification and legal certainty from the German and the European governments. What emerged quickly became known as the “Münchner Linie” (Munich Line), and consisted of three elements: (1) continuing on the migration path to free software; (2) reaching clarity and legal certainty about the patent risk; (3) asking others who support free software to join the effort and make their voice heard.

One week later, on August 11, Munich Mayor Christian Ude reversed the decision, resuming the call for tenders but also reiterating the need for clarification from Berlin and Brussels on the risks to free software created by the upcoming directive. LiMux was back on track again.

The law firm Frohwitter was commissioned by the City to assess the implications of a possible EU directive on patent litigation for Munich. It released its study on September 10, 2004, and looked at three different scenarios. [39]

- Under the current legislation, computer-implemented inventions are patentable, and therefore software can infringe patents. But because patent litigation is costly, potential gains from licensing are low (since only certain functions of a program can be protected). Furthermore, infringing functions can be replaced by non-infringing implementations. In this context, the study estimated that the risk of the City of Munich becoming the target of a patent lawsuit was low.

- If the EU Parliament draft of the directive were passed, such risk would be further diminished because the City does not use its software in the production of material goods. On the other hand, the study anticipated problems due to contradictions within the draft, which would create legal uncertainties and possibly bring the EU and its member states out of compliance with the WTO Agreement on Trade Related aspects of Intellectual Property (TRIPS), leaving the EU and its member states open to compensation claims by other TRIPS signatories.

- If the EU Council draft were passed, the main effect would be to write current practice into law, thereby increasing legal certainty but not significantly changing the larger picture. Under this scenario, the risk assessment is the same as in the first scenario.

In conclusion, the study denied that the City’s migration to free software created a higher risk of exposure to patent infringement lawsuits. That risk does not differ from that of proprietary software. Here the distinction between patent and copyright plays an important role. The fact that FOSS source code is open makes it more vulnerable to copyright infringement claims—potential litigants can scan the software for infringing snippets of code. This is the basis of several legal disputes and challenges to FOSS (see Jennifer Urban’s contribution to this report). Patent infringement claims, in contrast, have to be based on a functional analysis of the software unrelated to the source code—a situation of equal jeopardy for free and proprietary solutions. In practice, proprietary software companies have been targeted by patent litigation; GNU/Linux, to date, has not, even though it has been in use for over ten years. Claims against the Linux operating system kernel are especially unlikely, Frohwitter argued, because most of its functions date back to the 1960s.

To minimize the remaining risk, the study made several suggestions. All software procured by the City of Munich should contain an assurance that the software is unencumbered by third party rights. Such assurances could be strengthened by participation in a number of collective efforts designed to lower the legal uncertainty surrounding FOSS. Because patent infringement suits are regularly answered by a challenge to the validity of the patent, the study recommended that the City join efforts by the free software community to document its prior art—an important step in proving that an invention was not novel at the time of the registration of the patent. It also recommended that the City form alliances with other partners in the public sector to jointly fend off patent attacks. Finally, it recommended obtaining some form of insurance to cover litigation costs, but expressed ambivalence about new insurance products that cover claims arising from patent infringement.[40]

In the worst case scenario, a patent attack would prohibit city staff from using a specific function of a given computer program. The city would then either have to pay the licensing fees for that function or replace it with a non-infringing implementation.

In August 2004, the New York‑based company Open Source Risk Management (OSRM) also released a report on this issue, echoing the results of the Frohwitter study. The OSRM study also found that patent risks should not deter users from migrating to Linux, even in the US. According to the study, “not a single software patent fully reviewed and validated by the courts is infringed by the Linux kernel.” Although it determined that “283 software patents not yet reviewed by the courts could potentially be used to support claims of infringement against Linux,” the study concluded that “this is not a level of potential infringement greater than that of proprietary software.”[41]

The research company Gartner also weighed in on the Munich question. “Legal risks mostly come from U.S. patents, and no vendor with relevant patents seems to have shown any interest in threatening or initiating a lawsuit,” said Andrea Di Maio, Research Vice President at Gartner. Speculating about Munich’s motivations, Di Maio recommended that cases for migration not overrate patent‑related risks. Indeed, Gartner favored shifting the argument from risks to benefits: governments needed to pay special attention to “any positive impact that a large‑scale migration might have on local economic development, the competitiveness of the city or region, and similar issues.”[42]

The controversy around software patents and LiMux caused mixed reactions among the free software community. There were those who saw it as a panic reaction, out of proportion to the actual cause, and irresponsible in raising unfounded worries. After all, IBM is involved in LiMux, and what contender would dare start a patent suit against such a patent-rich corporation?

Others argued that it would be irresponsible not to take the risk seriously, pointing to cases in Sweden and the UK where public administrations had been involved in software patent lawsuits already. Munich will subcontract much of its software development to SMEs, which are not protected by large patent portfolios against claims.[43] Others praised the Munich City politicians for skillfully leveraging the attention that LiMux has attracted in order to influence the European law making process.

The German free software industry association LIVE spoke of an overreaction, but at the same time welcomed the escalation of the discussion on software patents.[44] Indeed, LiMux has become a widely cited example of the policy discrepancy between the German government’s use and encouragement of free software and its promotion of the European patent legislation, which would certainly not improve the climate for free software development and utilization.

In the end, the Frohwitter study had a reassuring effect on the City Council. On September 29, 2004, it confirmed the original vote to proceed with the migration.

First Results and Next Steps

The first phase of the migration started in mid-2004. The first users in Munich’s public administration are experiencing tangible results on their desktops.

The Europe-wide call for tenders for support and maintenance of the standard basic clients was concluded at the end of 2004. After a first round of negotiations with the bidders, modifications of the offers and a second round of negotiations, the decision was to be announced in March 2005. IBM and SuSE, who volunteered their support in the production of the migration plan, were considered strong candidates. Among proprietary software vendors, only Microsoft participated in the bidding. Unlike most calls for tenders, the specifications in the LiMux cases were general at first, and were being detailed in the course of negotiations with the bidders. Procedural rules have also been applied in ways to better accommodate freelancers, explains Schießl.

The final decision announced on April 14, 2005, came as a bit of a surprise to many. The winner for this contract was not IBM but a consortium of the two SMEs, Softcon and Gonicus. They will be deploying not SuSE but Debian GNU/Linux, the freest of the Linux distributions. LiMux Project Lead Peter Hofmann was very happy about the strong interest in the call and the high quality of the bids. They confirmed, he said, that Munich is on the right track. “The market showed that Linux on the desktop is not an exotic solution. With the planned migration the goal of the largest possible vendor independence can be reached while at the same time ensuring professional IT operations by the Bavarian capital.”[45]

The call for training materials and the e-learning platform, and a third call for project controlling have also been concluded and are now in the second round of negotiations. Although it was decided to conduct the migration with the existing IT personnel, additional support was found to be needed for the migration of office applications. Nine new posts were created, seven externally and two internally. When the press reported the job openings, there was enormous interest.

The actual migration puts the end-users at the center. Communications, training and support are core tasks at this point. Although general information sessions for City staff have been conducted since the beginning of the project, more intensive user training and support have begun as the first desktops are migrated. Having learned from the previous phase, there are now clear boundaries for the project and clear roles of the departments. Key personnel are now continuously available.

The efforts to date have raised the level of acceptance of FOSS among end-users, but the difficulties of the actual migration and day-to-day support are becoming apparent to IT staff, and support among them has dropped. From this experience, project coordinators have drawn the conclusion that support is not reached once and for all but has to be strived for continuously.[46]

Other problems arose as well, including the entanglement of the LiMux project in plans for a general renovation and consolidation of IT services in Munich.[47] A major overhaul of an IT infrastructure cannot, of course, simply aim to reproduce the status quo ante. The ICT processes that the migration will re-architect in free software are themselves in flux. In March, 2004, City Councilor Christine Strobl (SPD) proposed revamping AfID into a comprehensive central IT service provider, in part so that IT units in the different departments could focus on their own areas of core competence. AfID, under this new regime, would help make the IT infrastructure more managable by standardizing products and moving applications to the web, as well as consolidating the management of IT projects and introducing ITIL processes[48] in order to increase transparency and comparability of IT processes.[49] While Strobl emphasized that this strategic reorientation of the city’s IT organization is unrelated to the migration to free software, the two projects are obviously linked. Changes in IT management will affect LiMux, just as LiMux, with its web-centric strategy and long-term commitment to open systems, will affect the more general modernization of the city’s IT services.

Next Steps

The second phase of the migration together with the newly announced software partners will start a bit behind schedule in fall 2005. Currently, system-management solutions for the clients and a user-management system are being established. The procurement procedures regarding the web-based re-implementation of the first specialized applications have also been announced by the municipality. And the development of an Office migration strategy has started, which will address the particularly difficult issue of consolidating and migrating MS-Office macros, forms and templates. (For example, the City’s letter-head was produced by an MS-Office macro, which is now being replaced by a web-based solution.)

One of the next big challenges ahead is migrating sensitive software concerning, e.g., data protection and professional data processing. Key to this process is maintaining the integrity and continuity of services. This will continue until 2007, and there is hope that, in the meantime, more FOSS applications relevant to these needs will become available. Especially problematic are areas like CAD and cartography, where free equivalents of standard proprietary solutions (AutoCAD, ArcInfo, ArcView etc.) do not exist. Specialized applications that interface with CAD software, for example, rely on APIs that are available only in Windows.

One of the big goals for the coming months will be to convince local software SMEs to adopt a Linux strategy. The main calls for tenders for the basic client and for training software were not something that a typical five-person free software company could handle, but the development of the special applications has traditionally been done by SMEs. Still, interest so far has been disappointing. In a survey among those companies who had worked for Munich before, about a quarter responded that they have Linux solutions ready. The other replies ranged from “We’ll develop it if other municipalities will use it too.” to “We won’t develop for Linux.” Windows-based software could be used for a transition period but, says Schießl, the goal is to use the market power of the city of Munich to bring its influence to bear on the local software industry and bring it around to FOSS.

Networking between the developer community, the city administration, and other city politicians is considered crucial by all participants. But that doesn’t mean it’s easy, as Green-party City Councillor Jens Muehlhaus found out.

Muehlhaus and Open Source consultant Hamid Shefaat initiated a community-building effort around the LiMux project.[50] Muehlhaus sent out the first invitation in May 2004 to the city’s IT departments, including AfID, and to Open Source companies (MySQL, PHP, and others). This led to charges by Social Democrats that the City Councilor was dangerously creating the perception that private friends would be favored in the allocation of public contracts. Plans for a membership fee of 12 €/person and 120 €/company, intended to cover server and other organizational costs, led to accusations that Muehlhaus was using LiMux to make money on the side. There were rumors that applicants had to belong to Muehlhaus’ association in order to stand a chance in the public tender, even though there was no such formal requirement. The SPD argued that the right-wing opposition party CSU might use the community group as a basis for accusing Muehlhaus of bribery and corruption, undermining the LiMux process as a whole. As a consequence, Muehlhaus was effectively prohibited from calling meetings. Only the administration itself, which is managing the migration, or companies interested in the process could issue invitations to such meetings.

Thereafter, Muehlhaus pulled out of the networking activities, and Shefaat—who also belongs to the Green Party—took over the organizing role. At Shefaat’s invitation, about 50 people from the developer community, companies and public administration came together on July 23, 2004. Hoegner of AfID was there to discuss the state of the project.

This gathering further angered the Social Democrats. An official complaint was issued by the City Directorate, which is affiliated directly with the mayor‘s office. The Directorate put a stop to all further networking efforts, reaffirming the administrations monopoly power on convening meetings. Hoegner, himself from an old SPD family, actively supports the community building around LiMux and was very unhappy about these developments.

Muehlhaus explains this turn of events by pointing to the vested power structure. The SPD had been in power in Munich, with a brief interruption in the 1970s, since the end of the Second World War. As a result, the administration is to a large degree social-democratic as well. Traditionally, they are used to concluding general framework contracts with large industry partners—Big Politics working comfortably with Big Capital. They dislike the idea of having to deal with a wide range of smaller companies, and in this case possibly even with the long-haired nerds still widely associated with free software. There were also worries that, in these open meetings with the community, internal and possibly secret information might leak. Finally, the SPD Councilors driving the LiMux project, like Christine Strobl and Heimo Liebig, did not themselves have contacts in the free software community. Strobl is head of the SPD Council faction, Liebig is the faction’s computer expert, who supported the migration on technical grounds. Their achievement is to have brought their party colleagues firmly behind the LiMux project. While they are open to the practical advantages of free software, procedurally they adhere to the traditional social-democratic way of joining big government to big business.

Ever since the SPD City Council faction held talks with IBM, the SPD has been perceived as favoring a framework contract with the multinational FOSS leader. Rather than having to deal with dozens of SMEs, the migration and all its component tasks could simply be given over to IBM. Observers see this as another explanation for the SPD preventing community meetings: they could potentially coordinate the power of the SMEs, and thereby call into question the rationale for a large, single industry partner.

All these presumptions may have been derived from long experience, but Munich politicians proved critics wrong. If the guiding principle of many public sector decisions in the past was: ‘No one will blame you if you buy from the market leader,’ LiMux breaks with this tradition as well. The contract for the basic client was awarded to two SMEs who joined together for the call. Gonicus is a 15 person company in the small town of Arnsberg, and Softcon is a Munich-based stock company with a staff of 120.

The project leads—Wilhelm Hoegner, Florian Schießl and Peter Hofmann—are convinced that networking with the community is essential for the success of the project. Hoegner would like to contract all the development and integration that AfID cannot do on its own to companies from the local community. All three of them regularily go to free software events like Systems and LinuxTag, presenting the project and looking for dialogue. And they are actively involved in some of the free software projects but as private citizens, not in their official capacities.

The final challenge of the LiMux project will be to share it. The experiences around LiMux, including elements like the Open Test & Validation Center, the training model, and the larger adoption plan and decision process will be provided to other municipalities and public administrations.

Conclusions

Open Source Adoption as exemplified by LiMux is a multi-layered process with a range of constituencies. In the LiMux case, although the political arena was very important, the driving force behind it were the technical departments in the public administration. LiMux confirms a lesson learned from many free software deployment projects: when making technological decisions, listen closely to the technologists. They have to build it, they have to make sure it is secure, stable and reliable, they have to maintain it, and they have to support users. Security, stability and reliability are also what users want, but the IT landscape is such that much of the technical meaning of those values is beyond the comprehension, and partly beyond the control, of the average user. Intimate knowledge of IT architectures and their maintainability usually makes the technical intelligencia opt for free software. For technical users, Unix-based systems are the norm, and GNU/Linux is the de facto standard for Unix (along with BSD preferred for security sensitive services).

In the 1990s, it was common for IT administrators, whether in a company or in the public sector, to simply install on their servers what they found most suitable to their tasks. In many cases, they were running free software without any explicit approval or awareness on the part of other departments and senior managers. Today these choices have become foregrounded, both in the sense that there is considerable work to be done to educate and integrate nontechnical staff into the decision making process, and in the sense that there is considerable opportunity for nontechnical staff to see FOSS as an extension of broader social and political values—such as independence from vendors. The LiMux experience strongly suggests that the adoption process works both ways.

In case of LiMux, Munich's CIO Wilhelm Hoegner took the initiative. He and AfID played the key roles in developing the software assessment studies, and later the detailed plan for migration. They provided the City Council with a solid basis for its decision making. Of arguably more importance, Hoegner took professional risks to defend the idea that free software is a viable alternative to Microsoft. Hoegner did so in City Council committee meetings and in public. And if it took his wife to convince committee members of OpenOffice’s user-friendliness, he also arranged that proof.

Both in the public and the private sector, the financial administration plays a decisive part as well. Bavarian Audit Office admonishments to the public administration to make use of the cost savings potential of FOSS wherever possible was an important, indirect, atmospheric factor in Munich’s decision making. LiMux showed that calculating the TCO of large-scale IT systems is not as easy as comparing prices for milk in three different supermarkets. Even the prices themselves prove flexible, as the last-minute reductions offered by both contenders demonstrated. Contractual terms and conditions can impact both initial and ongoing costs, as well as other complex elements of budgeting and public accounting. The technological infrastructure for the internal and external information and communications operations of an organization obviously has complex dependencies—not all of which were anticipated in the very extensive run-up to LiMux.

Decisions in the highly dynamic area of IT also have to take into account unreliable predictions about technological trajectories, markets, shifts in the global IP regime, and other ‘exogenous’ factors. The timescale therefore is crucial. The Unilog study showed no short term cost advantage of free software over Microsoft solutions. What looked like a nominal Microsoft advantage in the short-term, however, was perceived as a road toward dependency and hidden costs. Munich took a mid- to long-term approach, trying to capture some of the softer, indirect effects of its choice in applying what it called qualitative and strategic criteria. Taking into account these policy goals, the results of the study favored FOSS to a degree that surprised even specialists like Hoegner.

On the political level, the decision was recurrently and actively framed by another form of argumentation. “The Munich City Council was not just faced with a decision about operating systems but had to grapple with fundamental questions about monopoly or democracy. This issue stirs and polarizes people,” says Jens Muehlhaus (31, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen), the City Councillor who most actively promoted the LiMux project. Muehlhaus speaks of a wave of approval when David won against Goliath, but also of skepticism among the public servants on the receiving end of the migration.

Concern for the soundness and sustainability of Munich’s IT infrastructure and the budgetary implications of software choice, of course, also figured highly in the political arena. Over time, says Muehlhaus, the Greens and the SPD became confident that free software provided a sophisticated, secure, and cost-effective system with all the required features—as well as being easy to learn and compatible with the main proprietary data formats. In addition, the City Council has to take the local job market into consideration. Munich has traditionally had a strong IT industry, but lately companies like Siemens have started moving jobs abroad. While a Microsoft solution would not have created a single new job in the region, there is a fair chance that the free software choice will create new jobs and secure existing ones in a range of local small‑ and mid‑sized enterprises (SME). “With the decision for FOSS, there is a chance to create jobs in Munich and Europe. That was very important for us,” says Muehlhaus.

Munich Mayor Christian Ude (57, SPD), like some of the other Councillors, took some convincing at first. He covered his back with internal and external expertise, and then wholeheartedly supported Munich’s move to free software. He is obviously enjoying the attention the City Council’s decision drew domestically and abroad, including the personal visit by Microsoft CEO Ballmer. The fact that other major European cities are following in Munich’s footsteps confirms his idea that Munich is playing a vanguard role. One might project a sense of European solidarity vis a vis the US into this movement, but Ude rejects accusations of anti-Americanism. He points to US companies like Sun, which congratulated Munich for its decision in full-page ads.[51] While European public and private decision makers may primarily be concerned about Microsoft‘s misuse of its market dominance, there is a larger underlying conflict. The EU Commission anti-trust investigations against Microsoft have shown differences in the understanding of fundamental concepts of anti-trust between the EU and the US. Other current disputes arise around concepts of privacy. But in the end, free software is no more European than proprietary software is US American. Ude’s main line of public argument is anti-monopoly. He took the fact that both Microsoft and IBM/SuSE corrected their offers downward during the last phase of decision making to prove that competition is good for business.

From a business perspective the choice was as clear as from the technical perspective. There was only one competitor to free software: Microsoft. It was Microsoft that forced the city to introduce a new generation of IT in the first place by discontinuing Windows NT. While the city was willing to consider Windows XP, both on technical and economic grounds, a number of the features of the Microsoft path were problematic—vendor lock-in, privacy concerns about the software sending information back to Microsoft, and the new leasing arrangements especially. Offering price reductions did not only fail to meet the demands of the Munich decision makers, it was also especially untimely when news about the company’s war chest for public sector lobbying and refunding broke. Finally, the surprise visit by Steve Ballmer to Munich Mayor Christian Ude showed how desperately Microsoft wanted the contract. Without this visit the motion in the City Council might not have passed, says Hoegner.[52] Nearly all moves by Microsoft in the Munich process served to drive the city toward its competitor. It seems that in the many-layered processes of open source adoption, Microsoft is not only a strong enemy but at the same time the best ally of free software.

A last and decisive layer to the LiMux process are the users. On the server, free software is largely invisible to users. Migrating desktop systems on the other hand, obviously needs their active cooperation. They are the final proof of the pudding. Even if technologists are convinced of a given solution, it is users who have to feel comfortable with them in the end. Hoegner testing OpenOffice on his wife is emblematic of this approach.

LiMux was started by technologists working toward what seemed to them the right thing to do. This drew worldwide attention because it hadn’t been done before, not on this scale, and not on the desktops of a complete municipal administration. As early adaptors, they had to be willing to take the heat, and they did. As a consequence, LiMux brought Munich into the limelight. Struggles over issues ranging from international intellectual property regimes to the global business strategies of players like Microsoft and IBM all played out in the hallways of the Bavarian capital. Muehlhaus told me: “On the small-scale of municipal politics we were able to turn a very big screw.” He obviously enjoys being invited to other cities and countries interested in the success story of LiMux, where he repeats: “When David won against Goliath, that was fun.”

References

Homepage of the LiMux project

www.muenchen.de/linux

Introducing the LiMux project

LiMux – the IT-Evolution,

http://europa.eu.int/ida/servlets/Doc?id=17200

Jens Muehlhaus, Member of the Bündnis 90/Die Grünen faction, Municipal Council, Munich, presenting LiMux on the “Free Software in the Public Sector” panel at the Wizards of OS 3, 10‑12 June 2004, Berlin (audio and video recordings)

http://wizards‑of‑os.org/index.php?id=557&L=3

Client study by Unilog, final version, 2 July 2003 [in German]

Legal study "Rechtliche Bedingungen und Risiken der Landeshauptstadt München für den Einsatz von Open Source Software,” law firm Frohwitter, 10 Sep 2004. [in German]

http://www.ris‑muenchen.de/RII/RII/DOK/SITZUNGSVORLAGE/517379.pdf

KBSt/BMI, Migration Guide

http://www.kbst.bund.de/Anlage304428/Migration_Guide.pdf

A selection of free software projects in the German federal administration [in German] http://www.kbst.bund.de/OSS‑Kompetenzzentrum/‑,276/Open‑Source‑Projekte.htm

Ongoing reporting on LiMux on the Pan-European eGovernment Services site IDABC (Interchange of Data between Administrations) in the ...

Open Source Observatory News

http://europa.eu.int/idabc/en/chapter/469

... and in the eGovernment Observatory News

http://europa.eu.int/idabc/en/chapter/194

Open Source Policies in EU Member States and worldwide

http://europa.eu.int/idabc/en/document/1677/471

Notes

[1] Dr. Volker Grassmuck is a researcher at the Helmholtz-Zentrum fuer Kulturtechnik, Humboldt University Berlin and author of “Freie Software. Zwischen Privat‑ und Gemeineigentum,” Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, Bonn, 2002 (http://freie‑software.bpb.de/). The author owes thanks to many people of which Florian Schießl and Jens Muehlhaus have to be mentioned, as well as the editors Joe Karaganis and Robert Latham for (nearly) unending patience.

[2]20 % of companies in Germany (50% of large companies with more than 1000 staff) use GNU/Linux, another 5% use other free software. According to a study by market researcher Meta Group based on a survey of 354 companies with 50 or more staff, free software is still mostly used on servers but is on the rise on the desktop. Early adopters are infrastructure providers: telecoms, transport companies, retail and public administration. (Meta Group press release, Aktuelle Studie der META Group zum Einsatz von Open Source Software in deutschen Unternehmen 2004, 21.10.2004, http://www.metagroup.de/presse/2004/pm34_21‑10‑2004.htm)

[3] Der Linux-Entscheider Münchens. Punk im Anzug, Sueddeutsche Zeitung, 19 November 2004, http://www.sueddeutsche.de/kultur/artikel/341/43298/

[4] Ibid.

[5] LiMux – the IT-Evolution, p. 6, http://europa.eu.int/ida/servlets/Doc?id=17200

[6] For a selection of free software projects in the federal administration see http://www.kbst.bund.de/OSS‑Kompetenzzentrum/‑,276/Open‑Source‑Projekte.htm

[7] Schwäbisch Hall erregt mit Umrüstung auf Linux weltweites Interesse, Heise News, 26.02.2003, http://www.heise.de/newsticker/meldung/34859

[8] Bayerischer Oberster Rechnungshof, Jahresbericht 2001, esp. chapter 20, http://www.orh.bayern.de/Jahresbericht2001.pdf

[10] LT-Drucksache 14/9009 Nr. 2 Buchstabe d, 19 March 2002

[11] Hintergrund: Das Kooperationsabkommen zwischen dem BMI und IBM, 5. Dezember 2002, http://www.kbst.bund.de/Software/‑,72/IBM‑Kooperation.htm#Abschnitt_Hintergrund

[12] The Guide is also available in English: KBSt/BMI, Migration Guide, http://www.kbst.bund.de/Anlage304428/Migration_Guide.pdf

[13] “For Microsoft, market dominance doesn't seem enough,” by Thomas Fuller, International Herald Tribune, May 14, 2003, http://www.iht.com/articles/96289.html. See also a memo by Ayala from November 2003 discussing damage control in cases where governments and other major institutions are considering OSS alternatives to MS products (http://opensource.org/halloween/halloween8.php).

[14] During their most recent meeting at Davos in January 2005, it is safe to assume that Gates also raised the issue of the public sector market going open source in general and LiMux in particular.